North America View (2015)

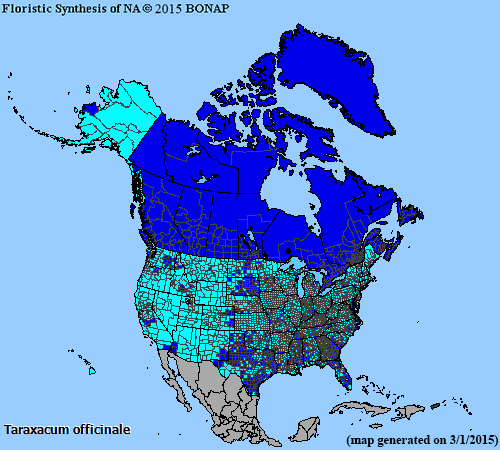

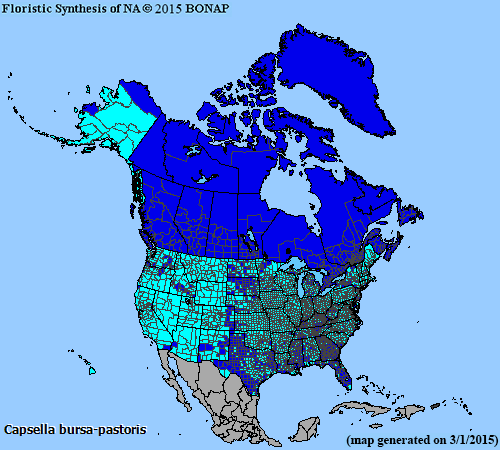

That the two most widespread North American vascular plant species, Taraxacum officinale and Capsella bursa-pastoris happen to be exotic, might concern some natural historians, weed specialists, plant ecologist, or others who believe that our native flora needs protection against all exotic invaders. Many thousands of scholarly papers have been written over the past several decades about the success of exotics, and their expansion into new locations around the globe, but nowhere more than in North America has a continental flora been so profoundly impacted by a greater percentage of exotics. Considering that half of the thirty most widespread species in North America are exotic, and slightly more than 20% of the entire vascular flora of North America is exotic (!), how is it possible that a native flora of nearly 19,000 species has become so infiltrated by exotics, nearly all of which are relatively recent arrivals. One reason is that many exotics are more successful at reproducing and dispersing than some of our native species. Another is that they arrived preadapted to the habitats we created for them through the alteration of pre-European North American landscapes.

Centuries ago, when the earliest foreign mariners faced the hardships of oceanic travel, some of the more courageous and fortunate ones successfully sailed and landed their vessels along a primitive North American shoreline, and knowingly or unknowingly, successfully introduced the first exotic plants. It is reported that at least some of these early travelers brought with them seed sacks filled with foreign grains. Unfortunately, these sacks of seeds were also laden with contaminated seeds and spores of other foreign species as well. As part of their cargo, they also carried dried roots and various plant parts, and in some cases live plants. At least some of the exotics that they brought happened to be prolific seed producers and able to disperse their seeds widely and rapidly across the landscape.

To a lesser degree, natural phenomena can also be blamed for its role in dispersing exotics. The vortices of cyclones, typhoons, hurricanes and even tornadoes can blow seeds and spores thousands of miles to and from landmasses around the globe. Rafting events too have been shown to be a source of species introductions, but these sources pale by comparison to the thousands of exotics introduced accidentally or deliberately into North America through agricultural and horticultural practices; which then begs the question, are all these exotics really that bad? A common theme that has penetrated the moral fiber of conservationists' protocol throughout the U.S. is to avoid exotics at all cost. In fact, for the past few decades, their clarion call has been to plant native species in lieu of exotics throughout the U.S.

In opposition, is an increasing number of individuals and institutions who are challenging this prohibition. A preponderance of plant enthusiasts do not believe that exotics are bad. In fact, many believe profoundly that the North American flora has benefited greatly from exotics. They argue passionately; what would our grocery shelves look like without exotic fruits, vegetables, or spices? How boring and colorless would our roadsides and pastures be without species like colt's foot, chicory, narrow-leaf cat-tail, sweet clover, Canadian horseweed, purple loosestrife, Queen Anne's lace, oxeye daisy, moth mullein, bull thistle, common dandelion, morning glories, and sow thistles? What would our lawns look like without exotic clovers, blue grasses, crab grasses, rye grasses; or our shrub borders look like without forsythias, lilacs, privets and bamboos to adorn them? And how drab would our botanical gardens, home gardens, and other manicured landscapes be without the displays of daffodils, tulips, peonies, pansies, poppies or hundreds of others handsome exotics? Many of these exotics are mentioned here, because they are included within The Hundred Most Thoroughly Distributed Species in North America; and arguably, in some cases, neither their beauty nor their societal benefits can be duplicated or replicated by native species alone!

Beyond the benefits mentioned above, many exotics add color and beauty to the artists' canvas, as much as they do for increasing species diversity itself. Neither can be duplicated solely by native plants. For those who have studied fine floral paintings of great artists such as Monet's Blue Water Lilies, or his Lilacs in a Vase; or Georgia O'Keefe’s Oriental Poppies; or Judith Leyster's Tulip; or Albrecht Dürer’s Tuft of Cowslips; or Jan Brueghel the Elder's, Flowers in a Vase; or certainly Vincent van Gogh's, Vase of Roses, know and understand the beauty that exotic species provide, and the appeal they bring to human society.

Conversely, plant enthusiasts who visit gardens that specialize in native species exclusively are generally disappointed by what they see as colorless, simplistic, boring and uninspiring. To compensate, some native gardens have introduced regional or national natives via seeds or living plants, in some cases from hundreds of miles away. These same gardens, however, prevent many beautiful plants indigenous to islands less than 90 miles away in the Caribbean from growing in their gardens. So what is the difference between plants introduced from a hundred miles away, several hundred miles away, or several thousand miles away?

Except for the relatively few highly invasive exotics that replace our native species and come to dominate associated habitats, proponents of exotics champion and promote the inclusion of exotics into our flora for all of the reasons stated above. BONAP would like to know your view. -JTK

rank 001 Taraxacum officinale |

rank 002 Capsella bursa-pastoris |

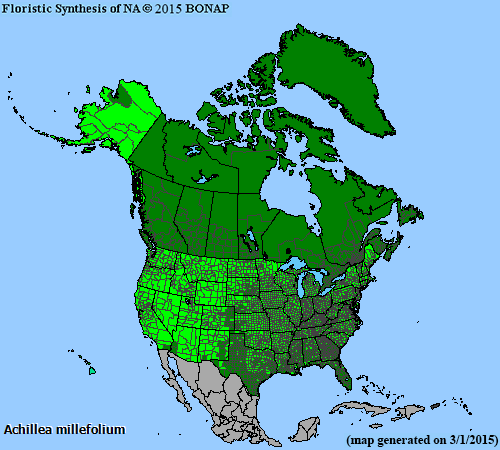

rank 003 Achillea millefolium |

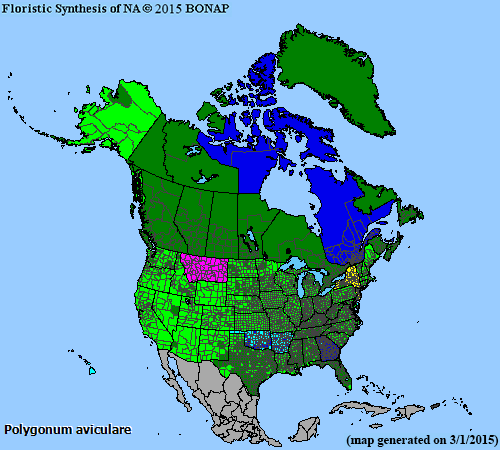

rank 004 Polygonum aviculare |

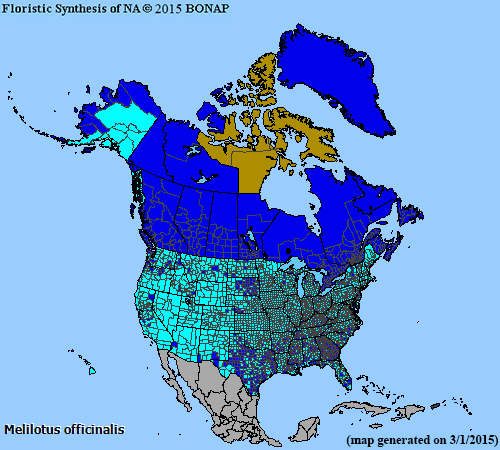

rank 005 Melilotus officinalis |

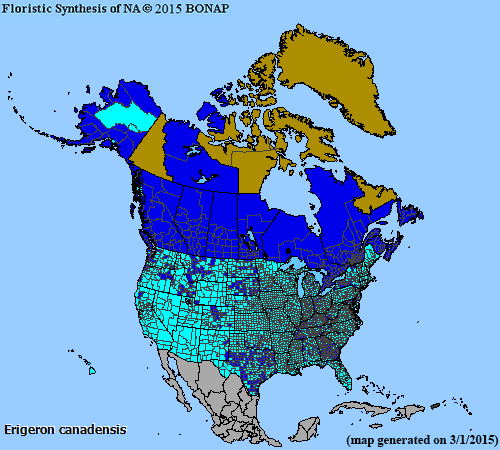

rank 006 Erigeron canadensis |

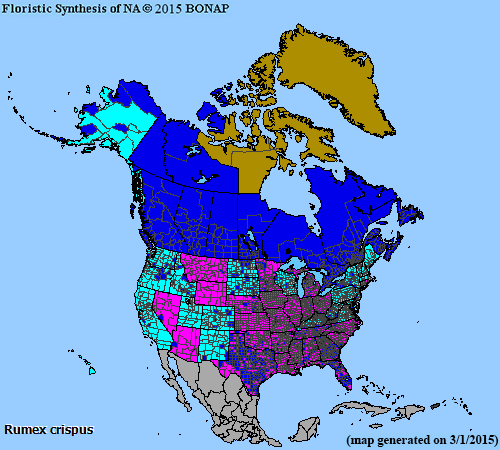

rank 007 Rumex crispus |

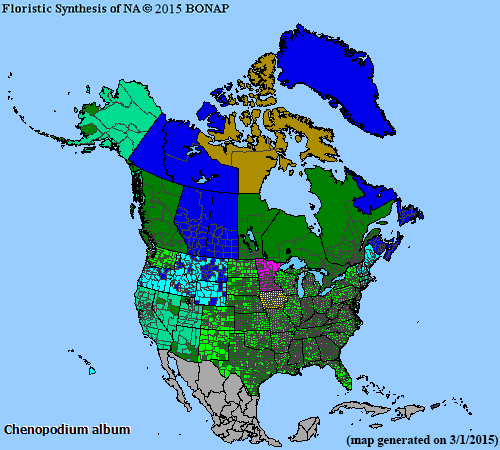

rank 008 Chenopodium album |

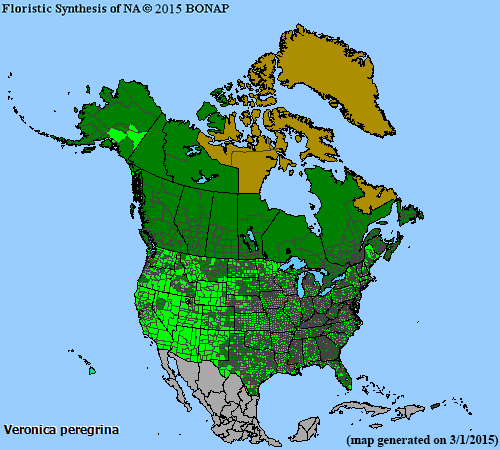

rank 009 Veronica peregrina |

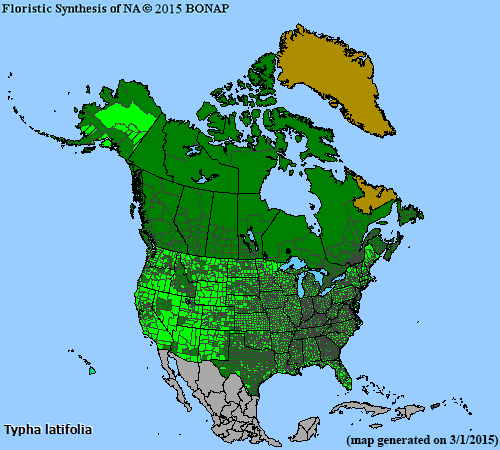

rank 010 Typha latifolia |

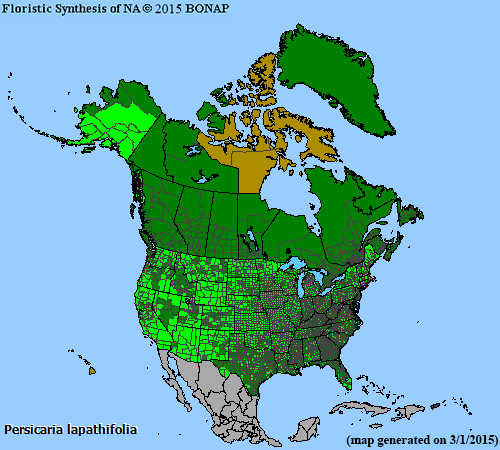

rank 011 Persicaria lapathifolia |

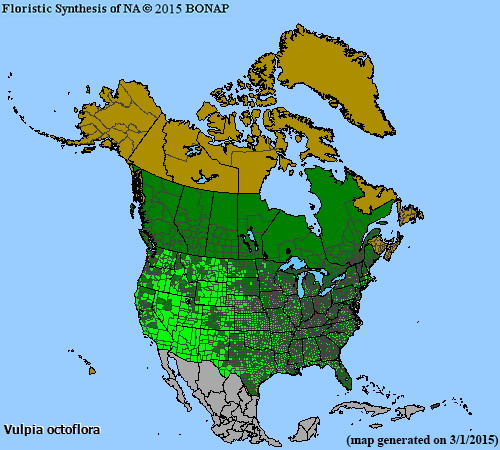

rank 012 Vulpia octoflora |

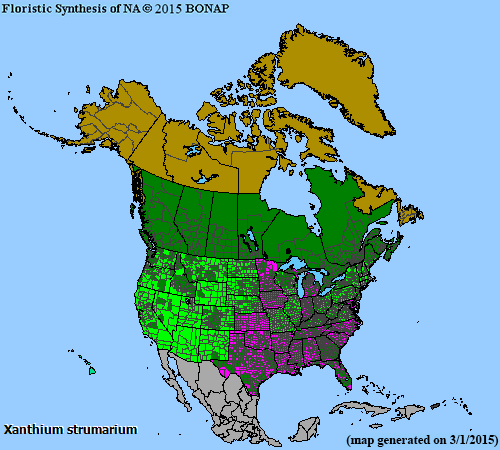

rank 013 Xanthium strumarium |

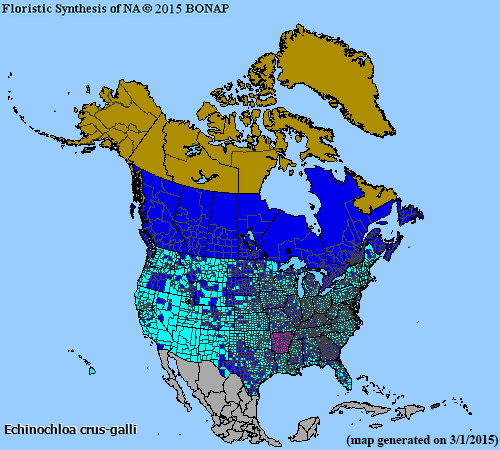

rank 014 Echinochloa crus-galli |

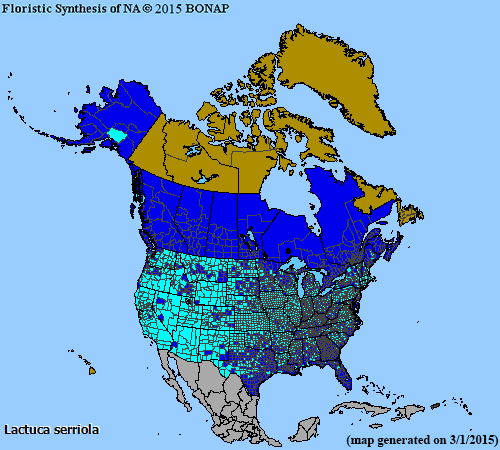

rank 015 Lactuca serriola |

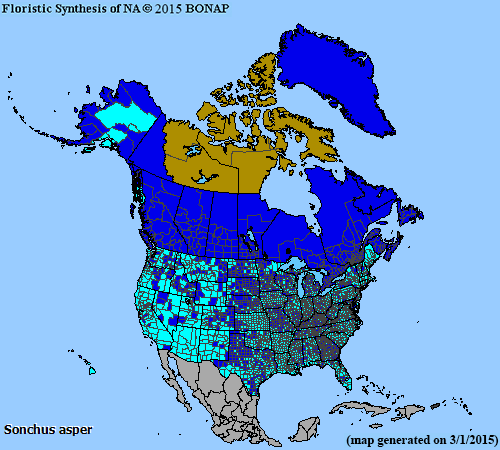

rank 016 Sonchus asper |

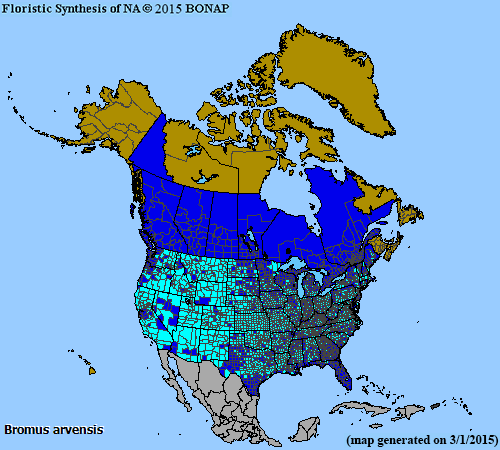

rank 017 Bromus arvensis |

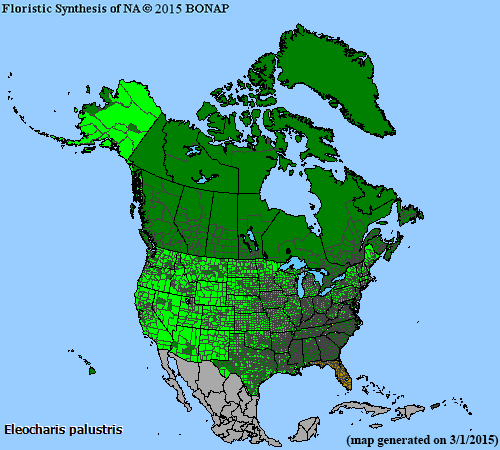

rank 018 Eleocharis palustris |

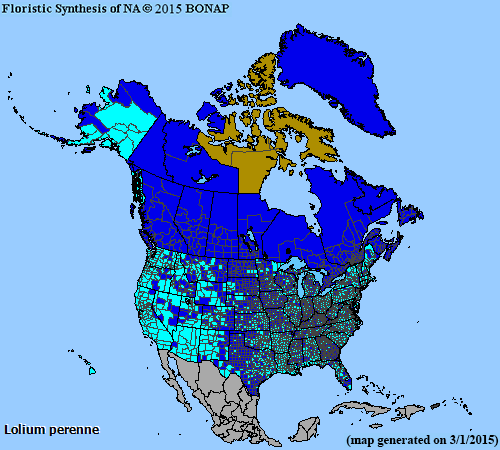

rank 019 Lolium perenne |

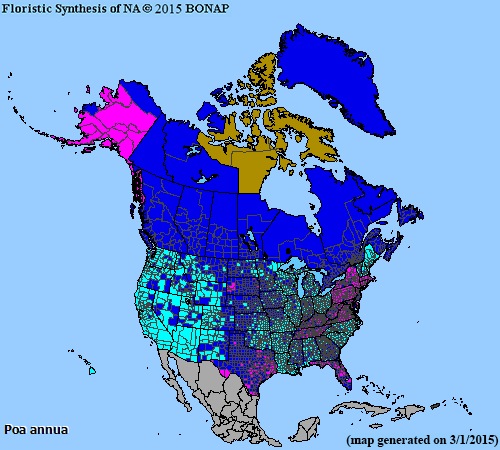

rank 020 Poa annua |

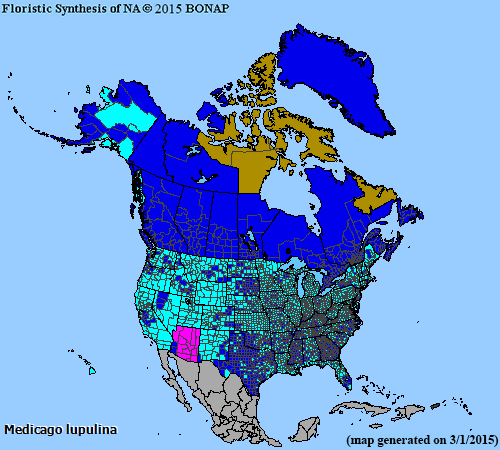

rank 021 Medicago lupulina |

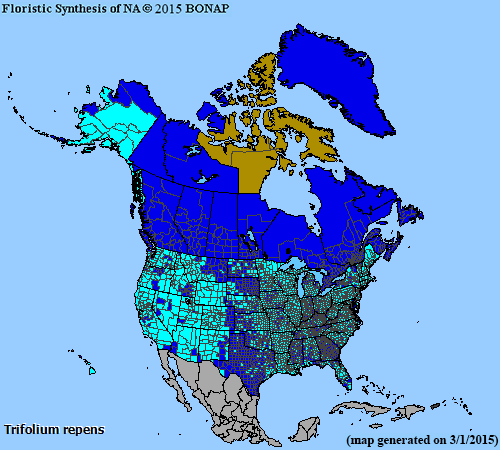

rank 022 Trifolium repens |

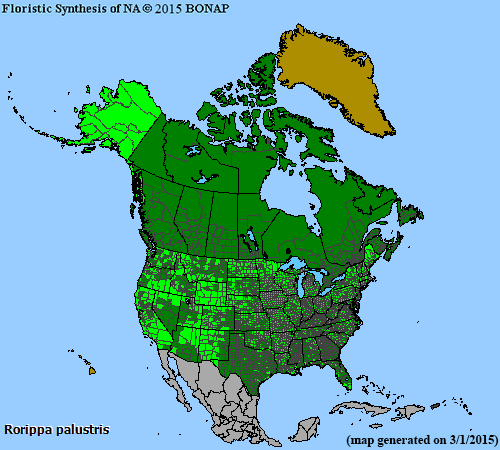

rank 023 Rorippa palustris |

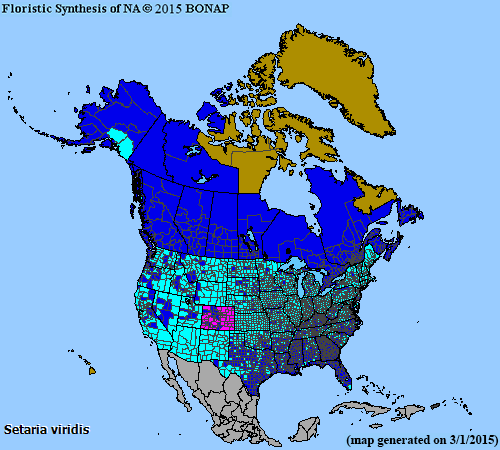

rank 024 Setaria viridis |

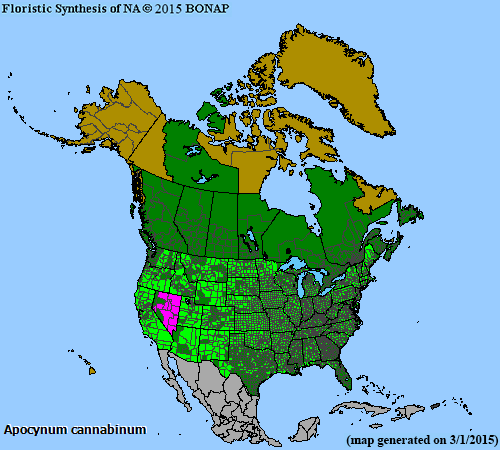

rank 025 Apocynum cannabinum |

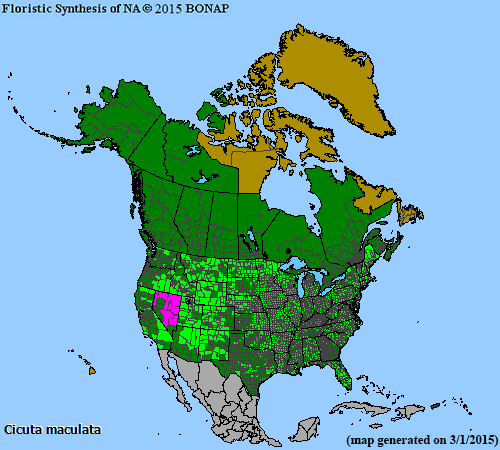

rank 026 Cicuta maculata |

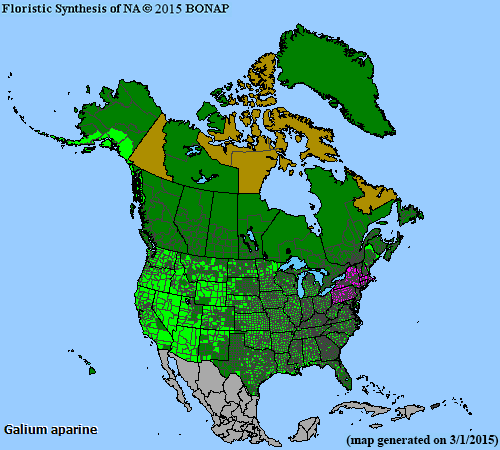

rank 027 Galium aparine |

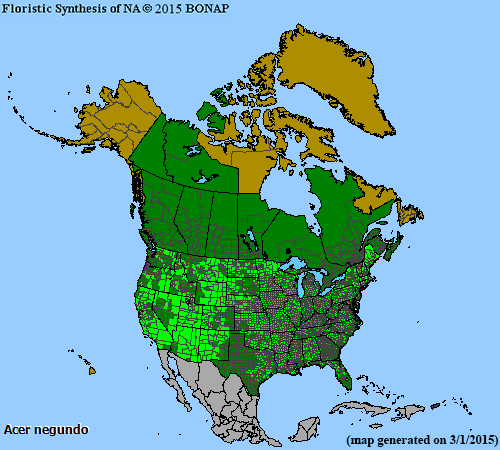

rank 028 Acer negundo |

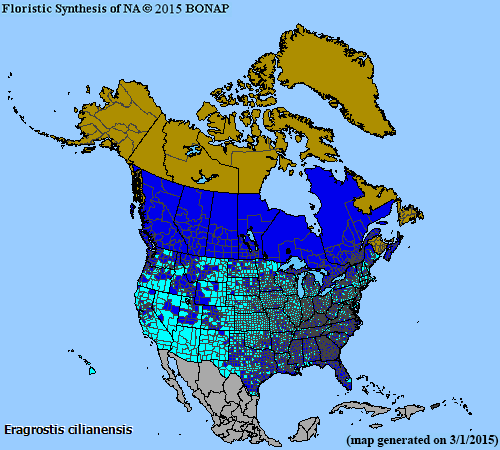

rank 029 Eragrostis cilianensis |

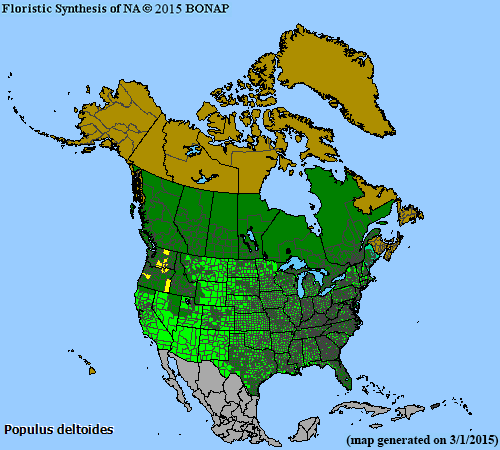

rank 030 Populus deltoides |

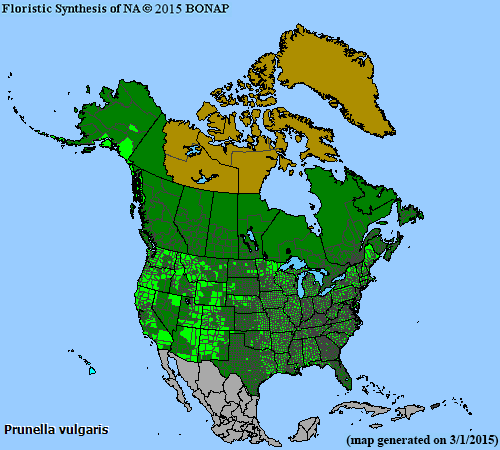

rank 031 Prunella vulgaris |

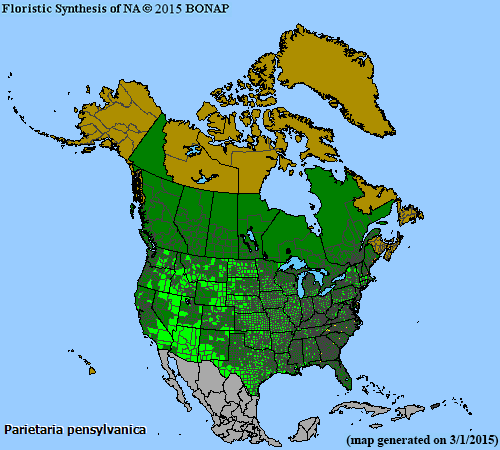

rank 032 Parietaria pensylvanica |

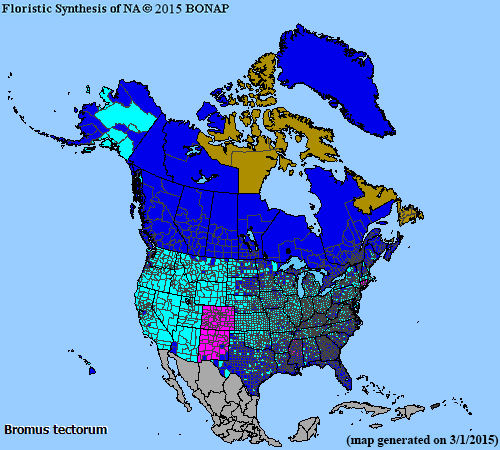

rank 033 Bromus tectorum |

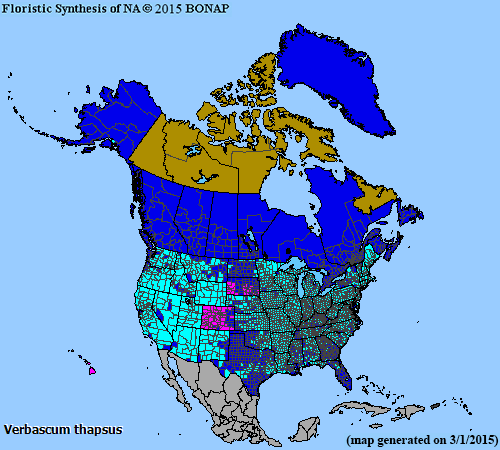

rank 034Verbascum thapsus |

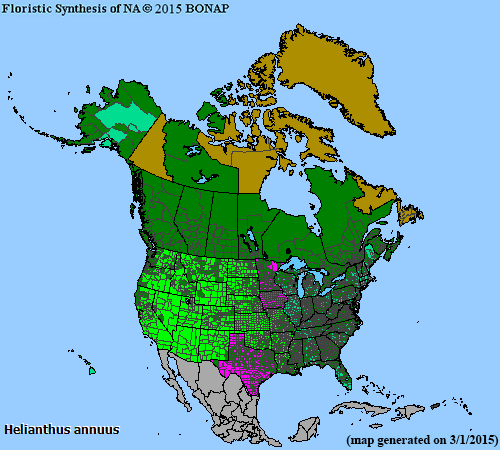

rank 035 Helianthus annuus |

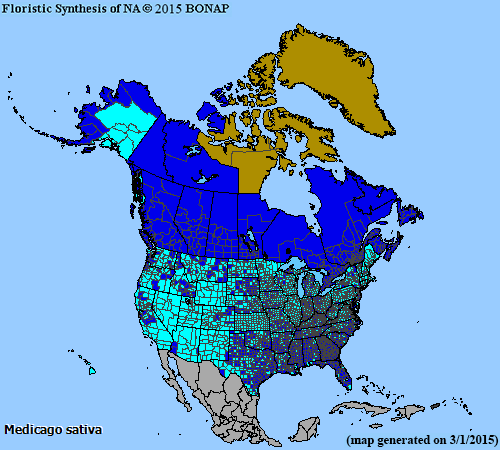

rank 036 Medicago sativa |

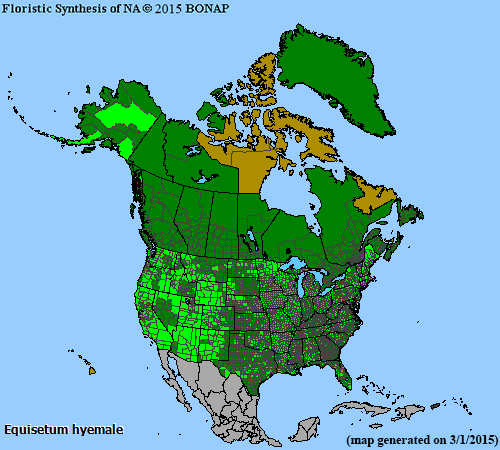

rank 037 Equisetum hyemale |

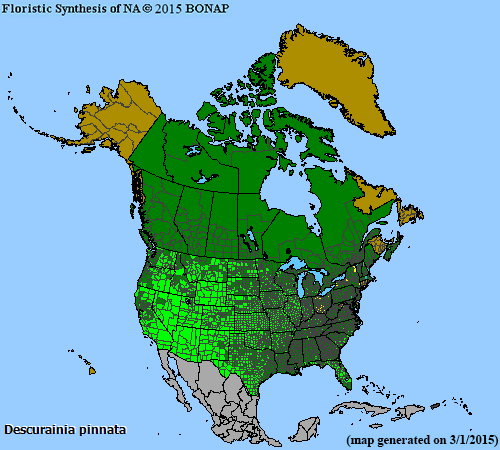

rank 038 Descurainia pinnata |

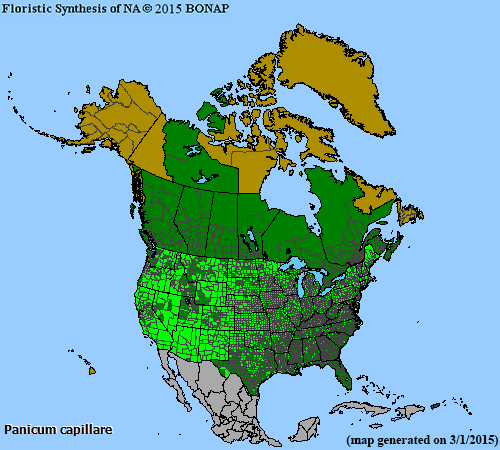

rank 039 Panicum capillare |

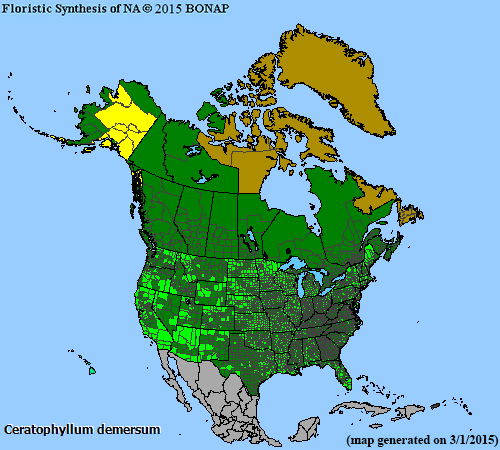

rank 040 Ceratophyllum demersum |

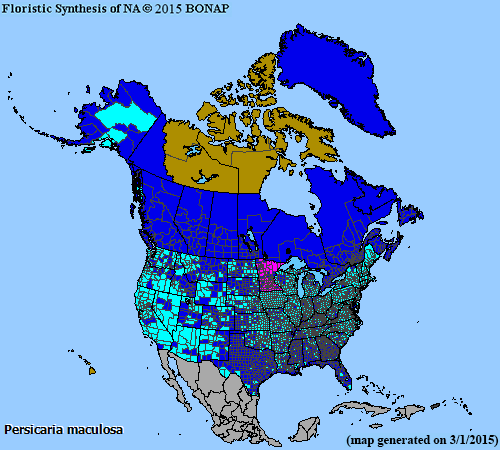

rank 041 Persicaria maculosa |

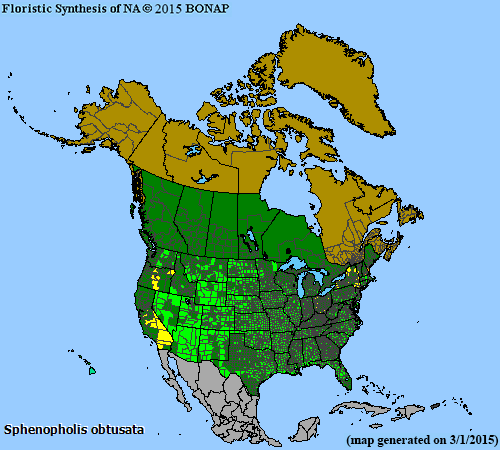

rank 042 Sphenopholis obtusata |

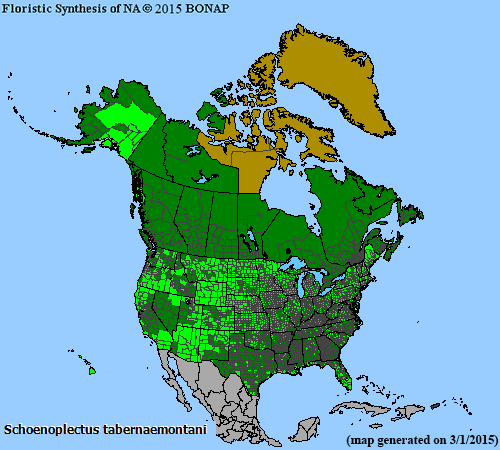

rank 043 Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani |

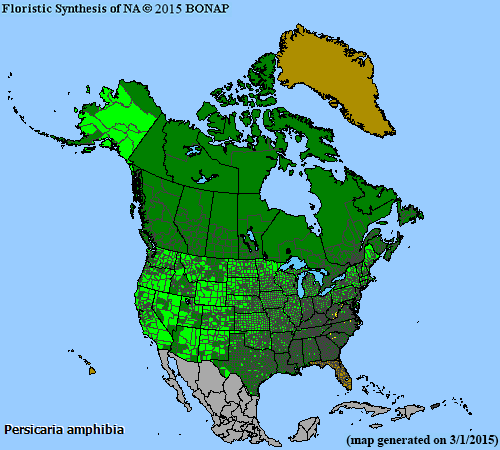

rank 044 Persicaria amphibia |

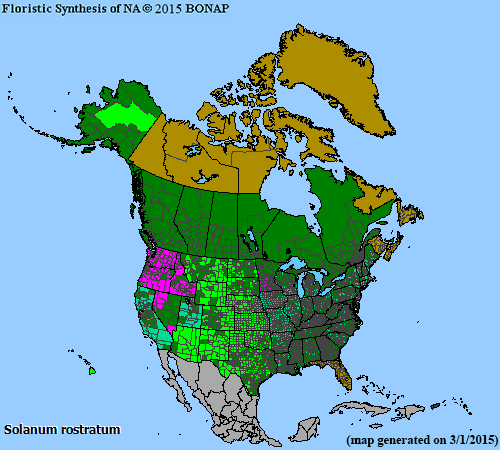

rank 045 Solanum rostratum |

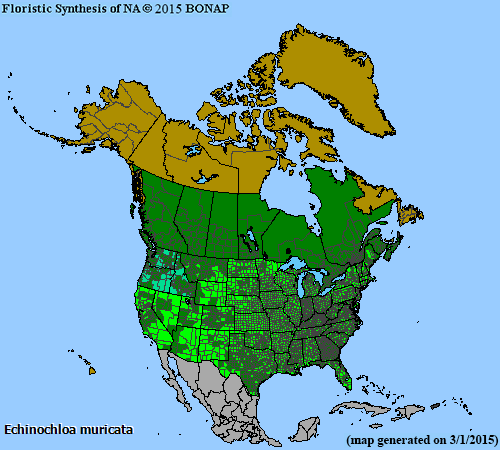

rank 046 Echinochloa muricata |

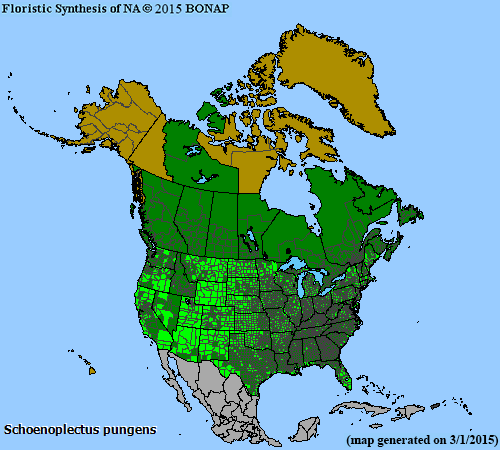

rank 047 Schoenoplectus pungens |

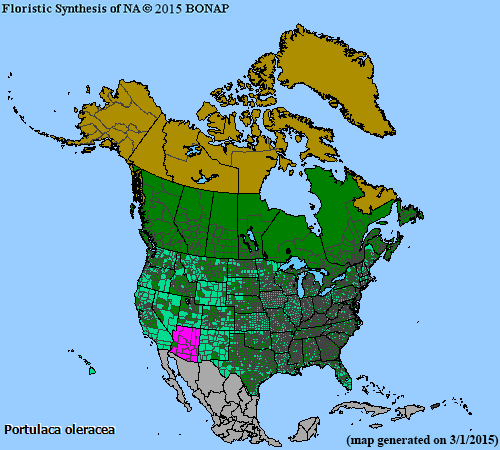

rank 048 Portulaca oleracea |

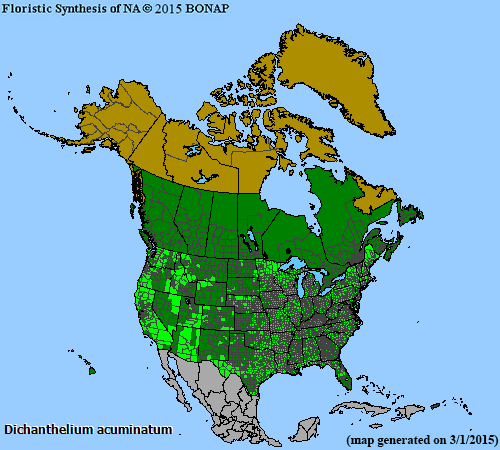

rank 049 Dichanthelium acuminatum |

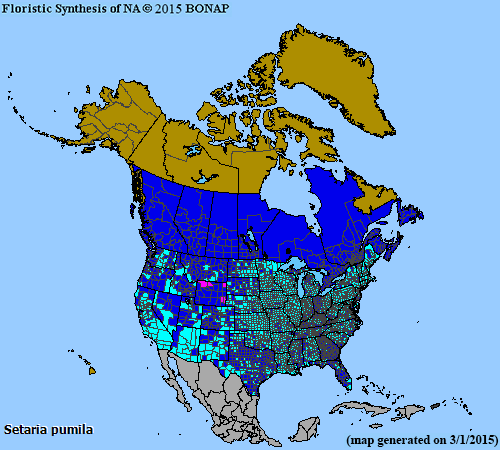

rank 050 Setaria pumila |

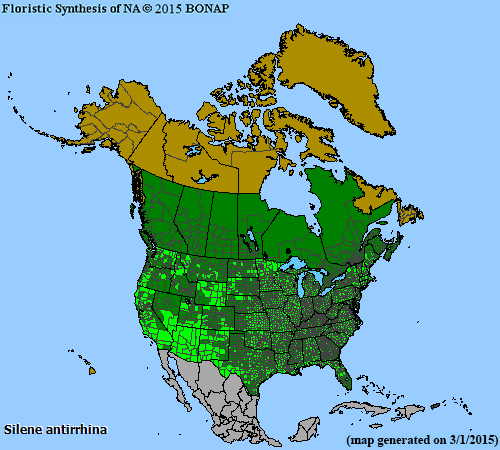

rank 051 Silene antirrhina |

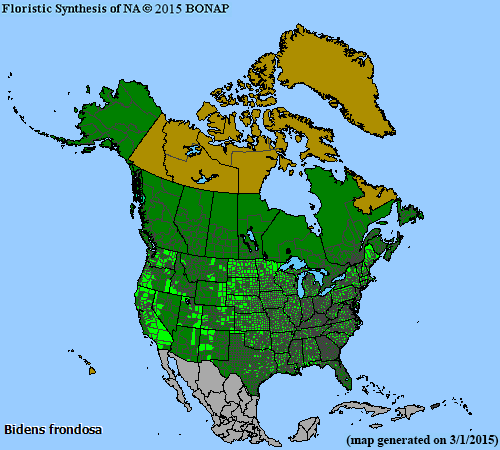

rank 052 Bidens frondosa |

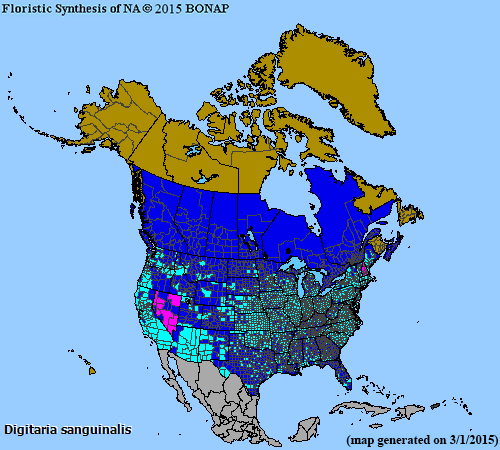

rank 053 Digitaria sanguinalis |

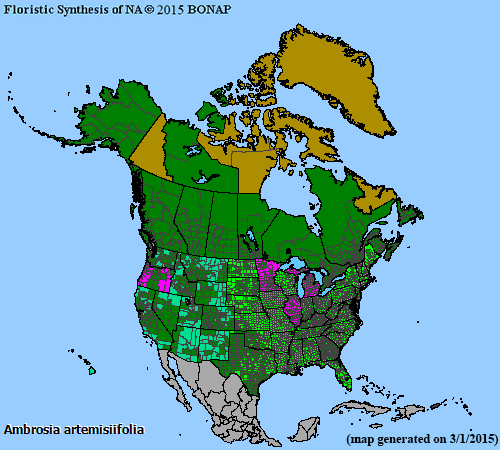

rank 054 Ambrosia artemisiifolia |

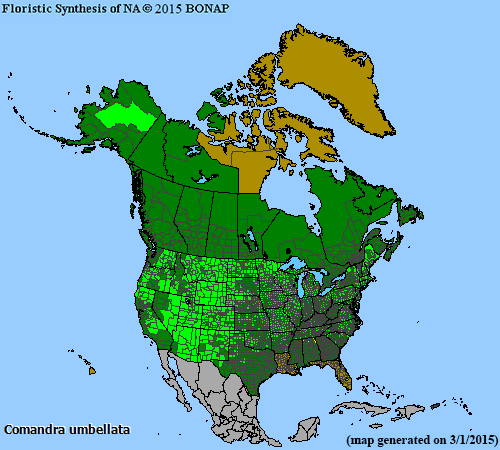

rank 055 Comandra umbellata |

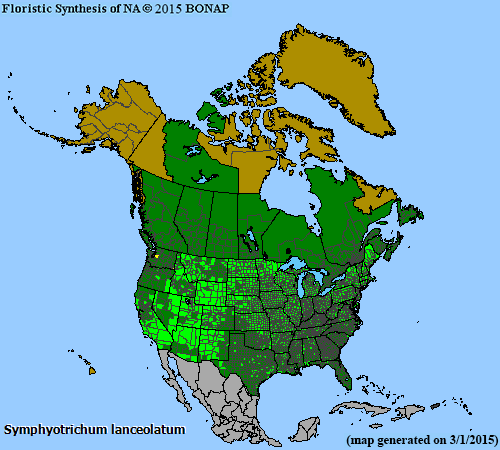

rank 056 Symphyotrichum lanceolatum |

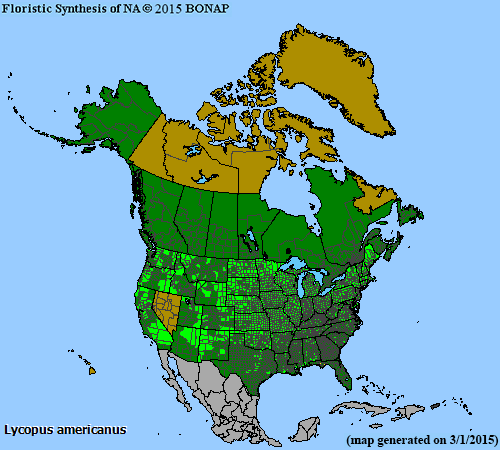

rank 057 Lycopus americanus |

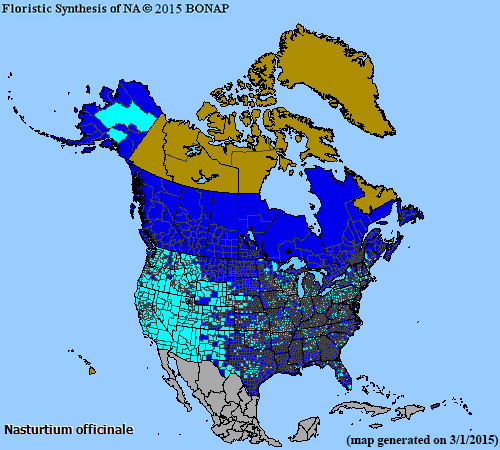

rank 058 Nasturtium officinale |

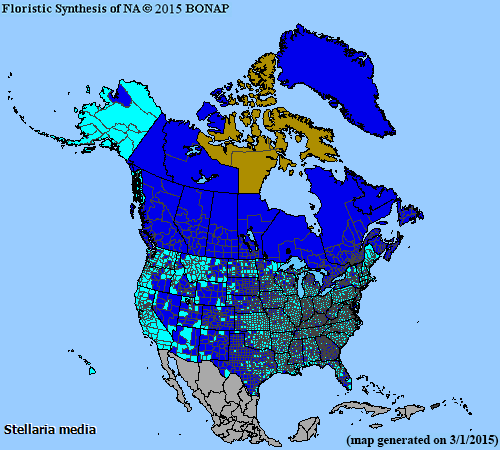

rank 059 Stellaria media |

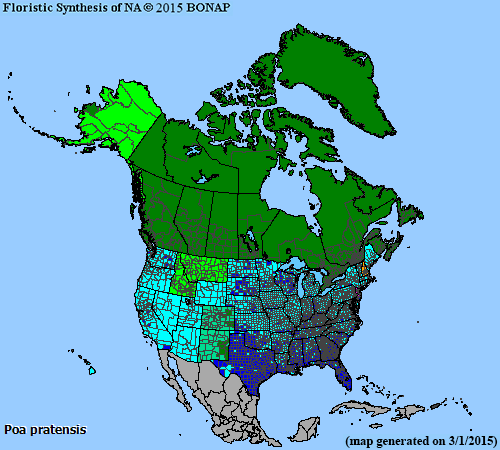

rank 060 Poa pratensis |

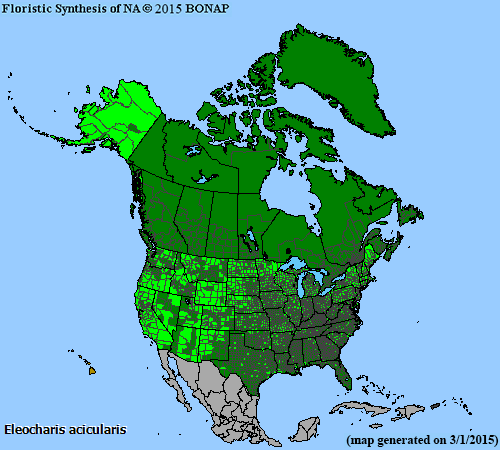

rank 061 Eleocharis acicularis |

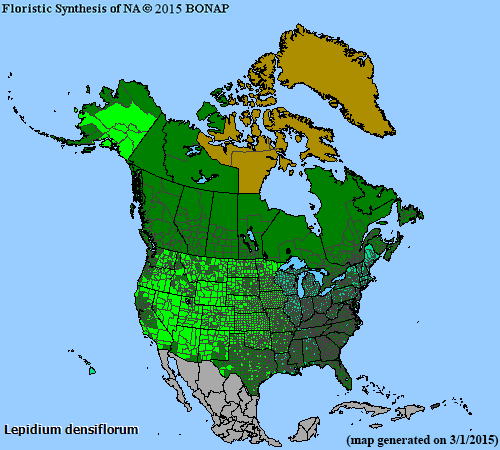

rank 062 Lepidium densiflorum |

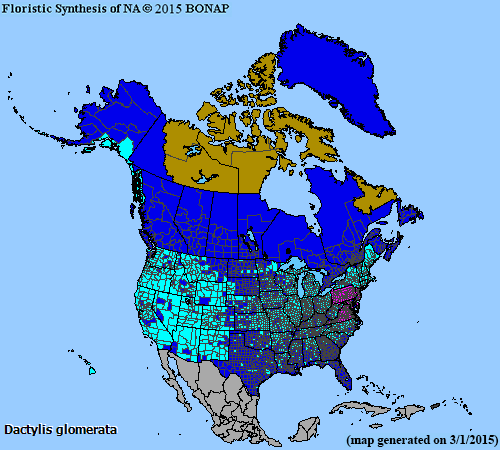

rank 063 Dactylis glomerata |

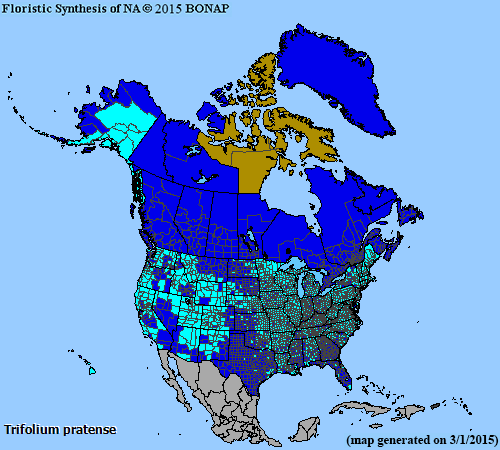

rank 064 Trifolium pratense |

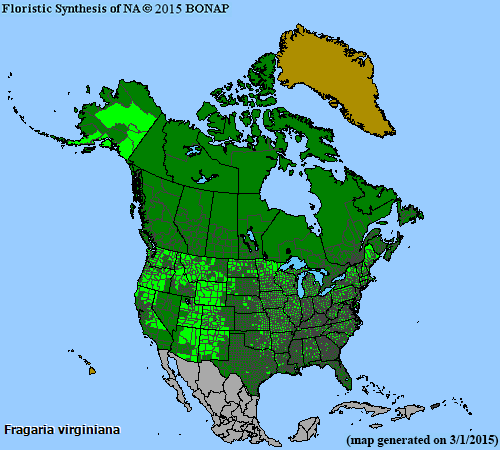

rank 065 Fragaria virginiana |

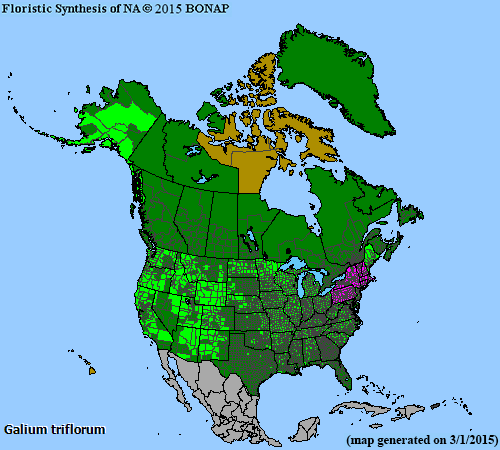

rank 066 Galium triflorum |

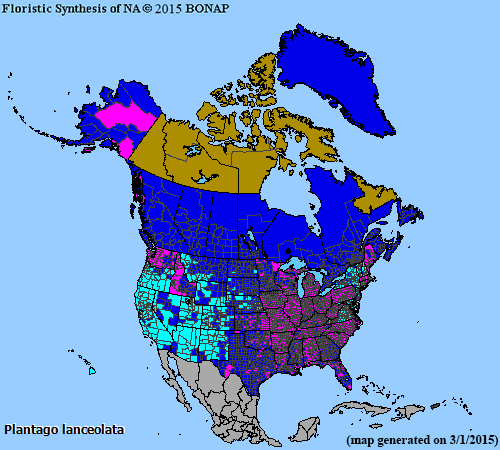

rank 067 Plantago lanceolata |

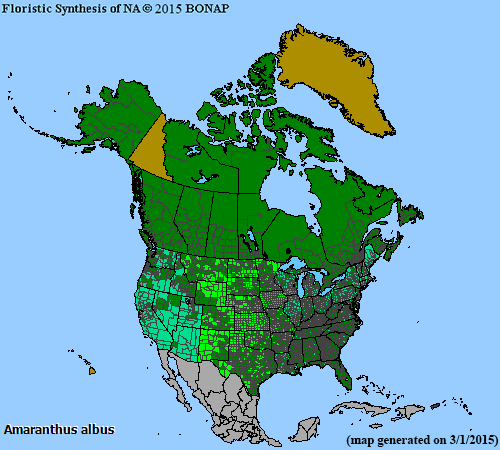

rank 068 Amaranthus albus |

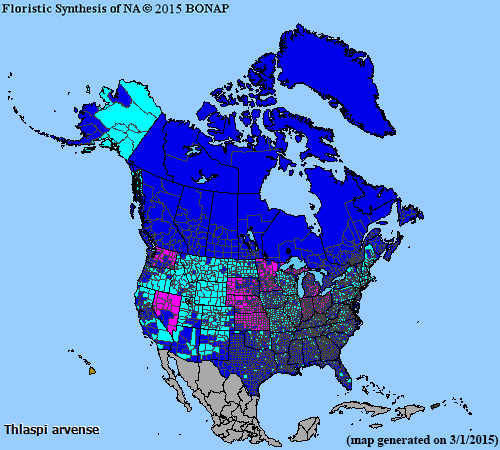

rank 069 Thlaspi arvense |

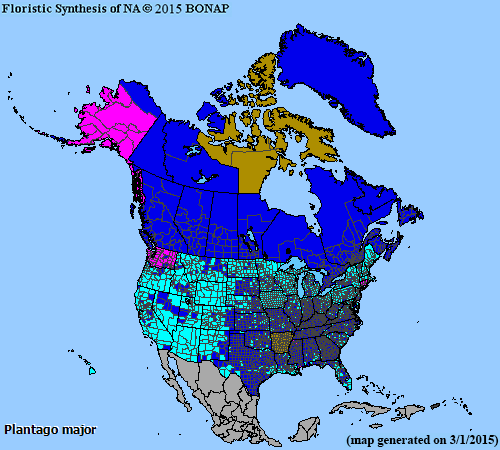

rank 070 Plantago major |

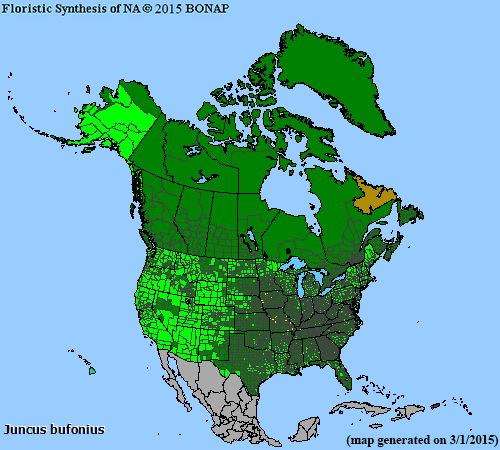

rank 071 Juncus bufonius |

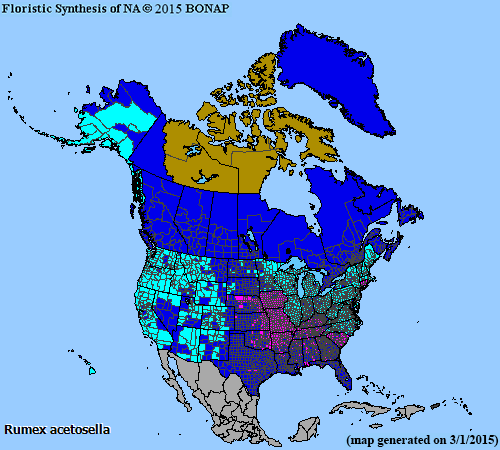

rank 072 Rumex acetosella |

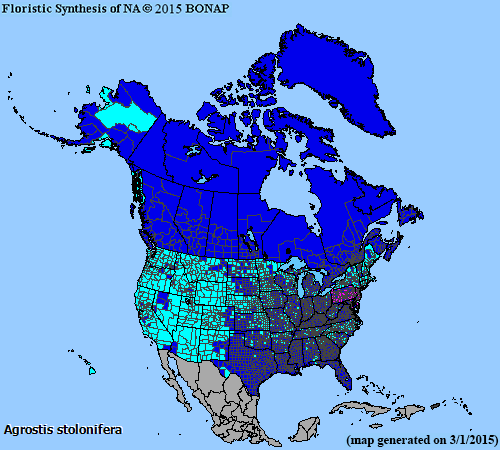

rank 073 Agrostis stolonifera |

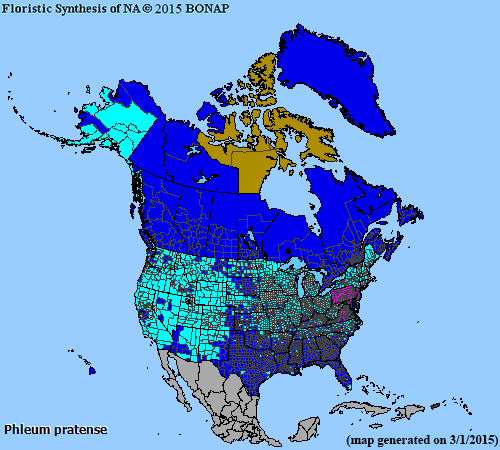

rank 074 Phleum pratense |

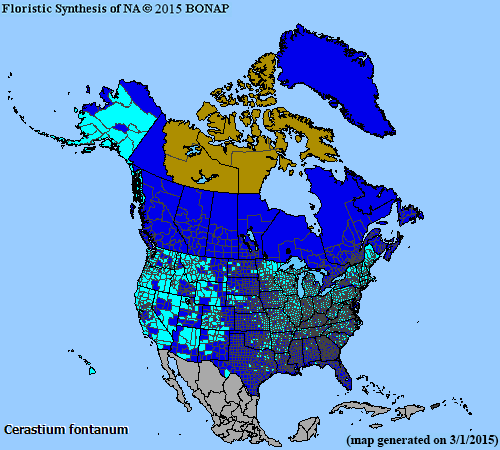

rank 075 Cerastium fontanum |

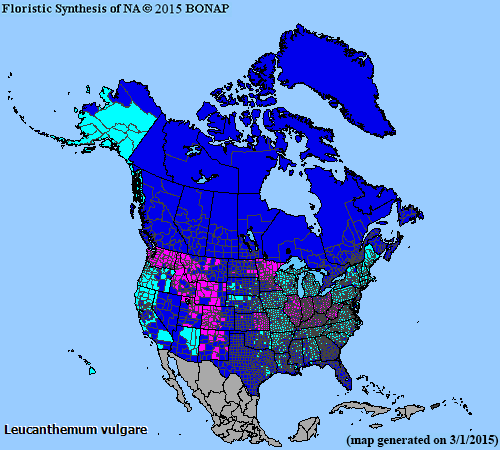

rank 076 Leucanthemum vulgare |

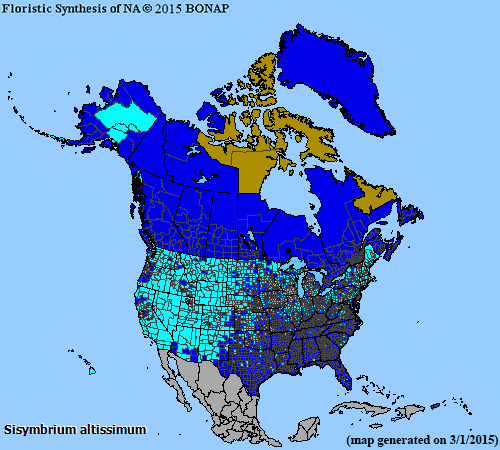

rank 077 Sisymbrium altissimum |

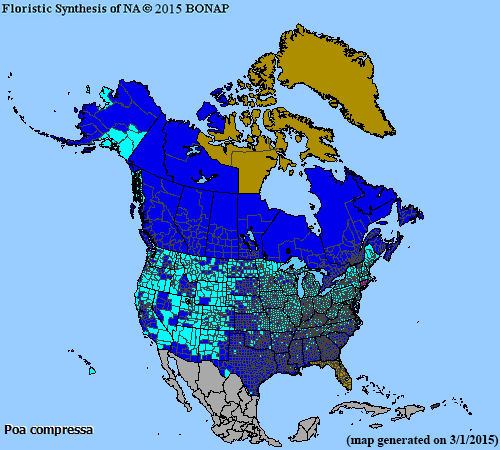

rank 078 Poa compressa |

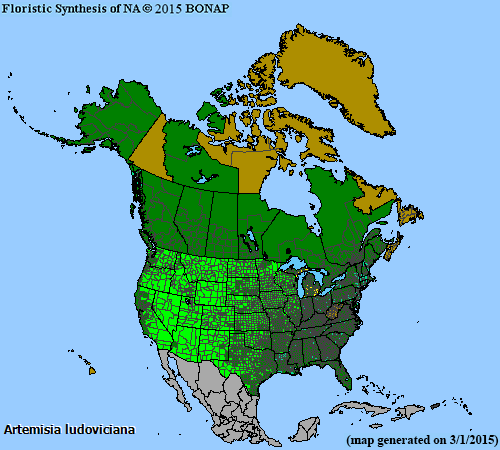

rank 079 Artemisia ludoviciana |

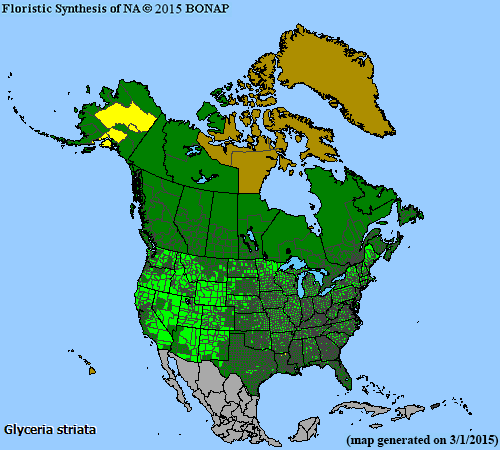

rank 080 Glyceria striata |

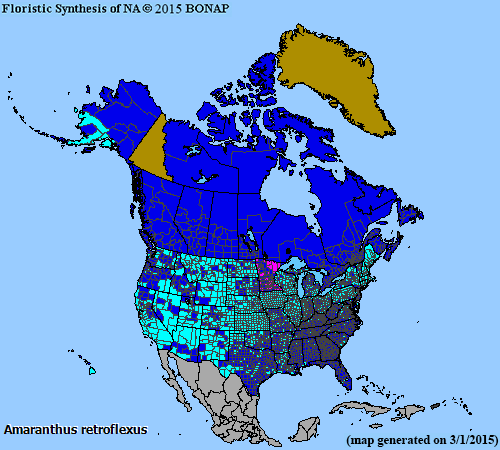

rank 081 Amaranthus retroflexus |

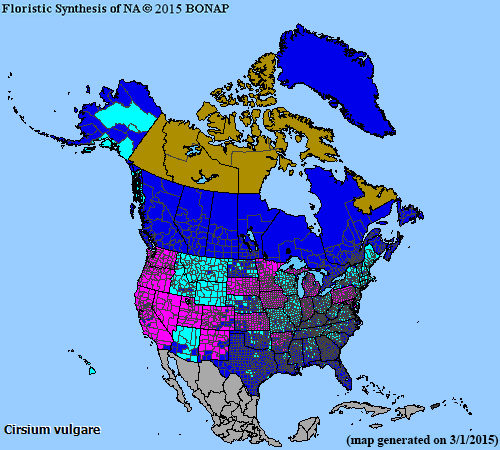

rank 082 Cirsium vulgare |

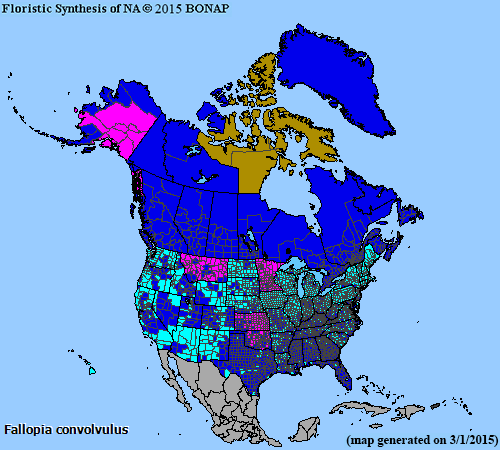

rank 083 Fallopia convolvulus |

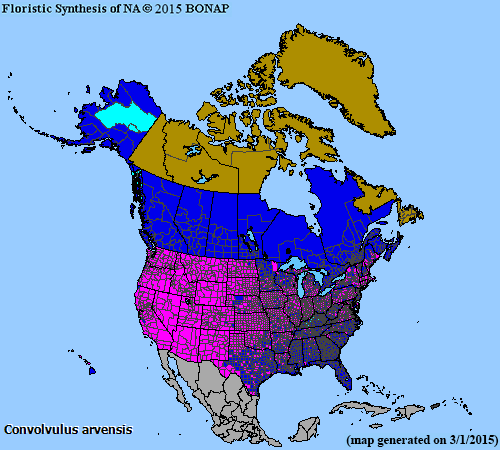

rank 084 Convolvulus arvensis |

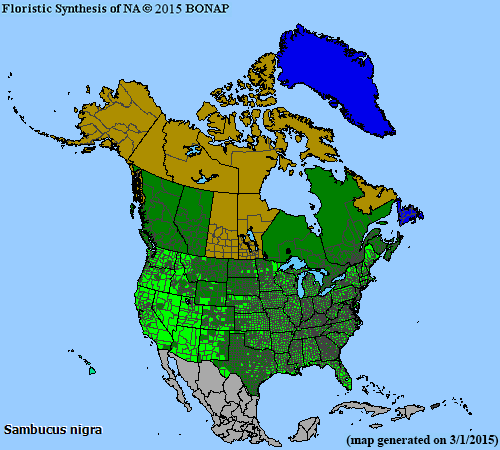

rank 085 Sambucus nigra |

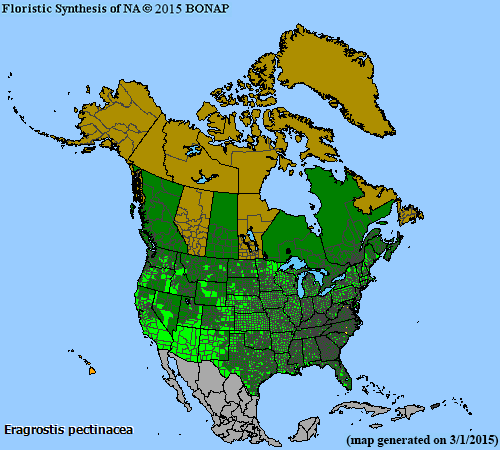

rank 086 Eragrostis pectinacea |

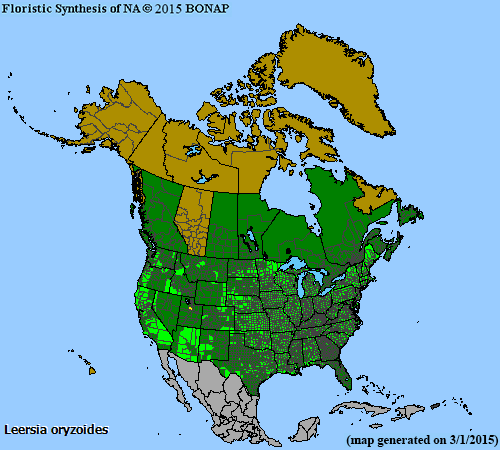

rank 087 Leersia oryzoides |

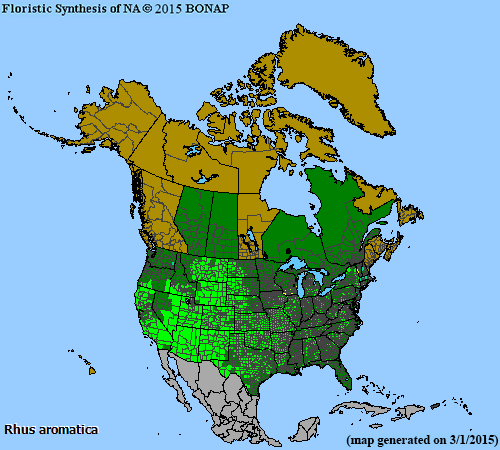

rank 088 Rhus aromatica |

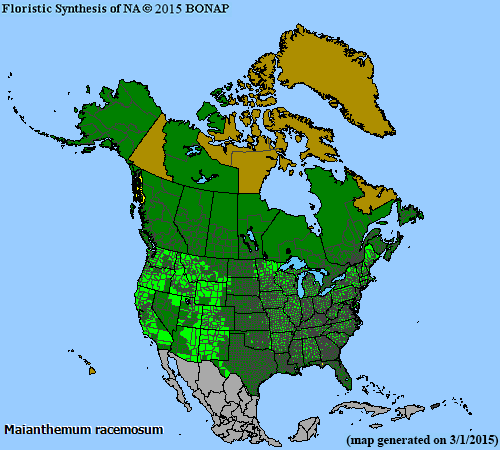

rank 089 Maianthemum racemosum |

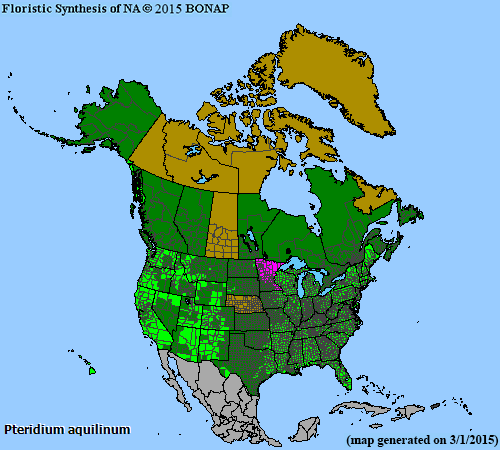

rank 090 Pteridium aquilinum |

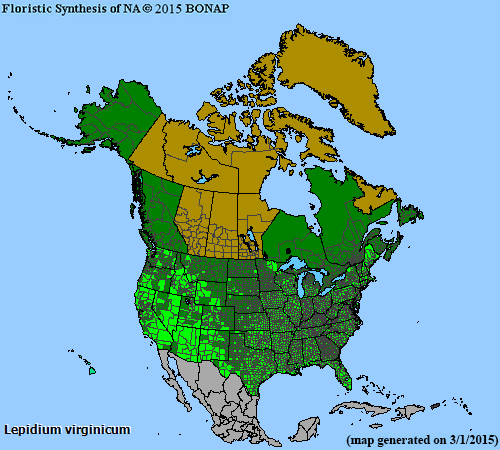

rank 091 Lepidium virginicum |

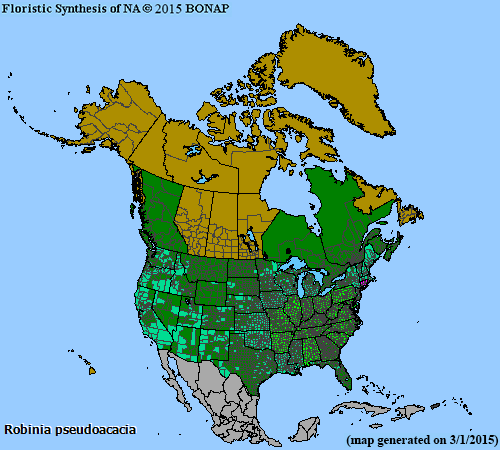

rank 092 Robinia pseudoacacia |

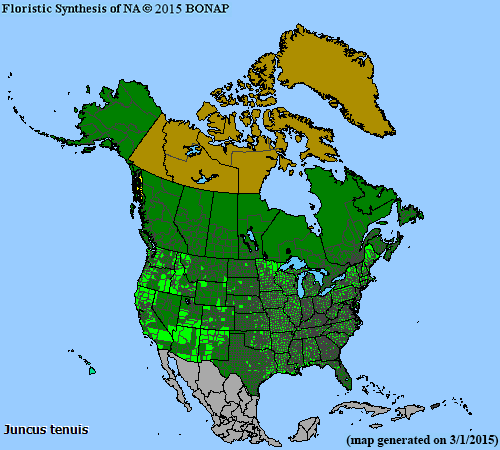

rank 093 Juncus tenuis |

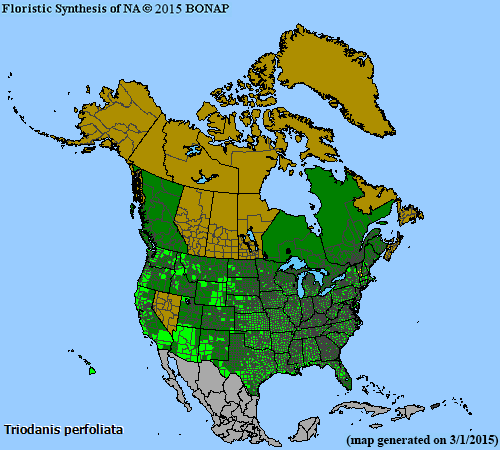

rank 094 Triodanis perfoliata |

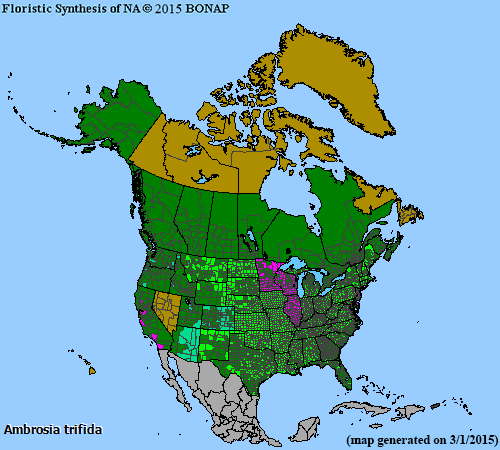

rank 095 Ambrosia trifida |

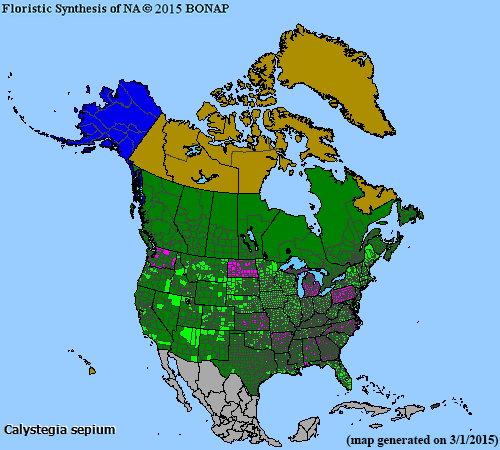

rank 096 Calystegia sepium |

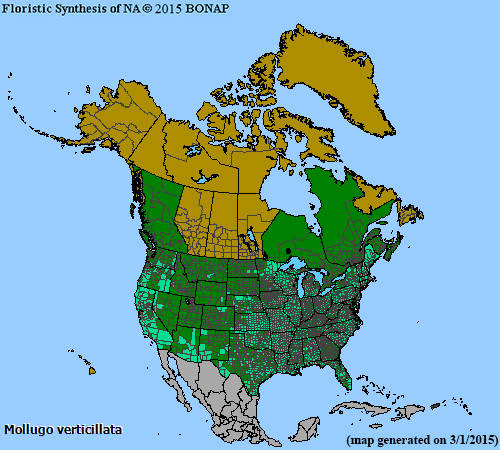

rank 097 Mollugo verticillata |

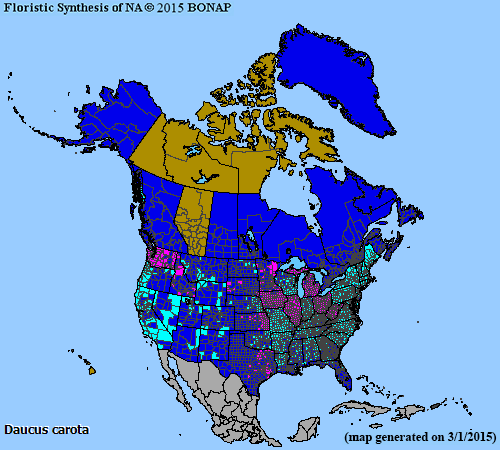

rank 098 Daucus carota |

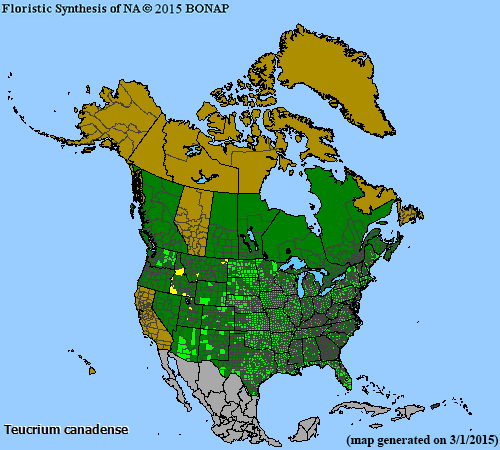

rank 099 Teucrium canadense |

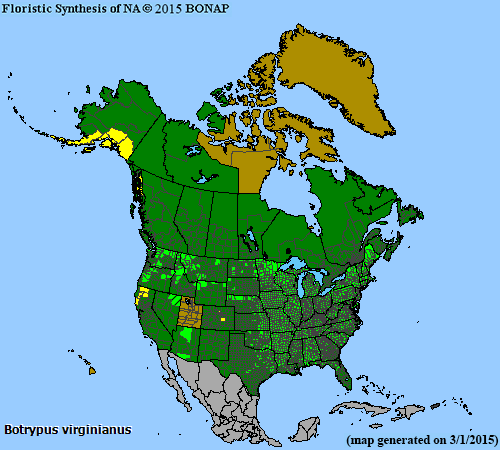

rank 100 Botrypus virginianus |

Last updated June 8, 2015.